Filesystem in Userspace (FUSE) born in 2001, enables users to create custom file systems in user space. By lowering the barrier to file system development, FUSE empowers developers to innovate without modifying kernel code. JuiceFS, a high-performance distributed file system, leverages FUSE’s flexibility and extensibility to deliver robust storage solutions.

In this article, we’ll explore FUSE’s architecture and advantages, tracing the evolution of kernel file systems and network file systems that laid the groundwork for FUSE. Finally, we’ll share JuiceFS’ practical insights into optimizing FUSE performance for AI workloads. Since FUSE requires switching between user space and kernel space, it brings certain overhead and may lead to I/O latency. Therefore, many people have doubts about its performance. From our practical experience, FUSE can meet performance requirements in most AI scenarios. We’ll elaborate relevant details in this article.

Standalone file systems: Kernel space and VFS

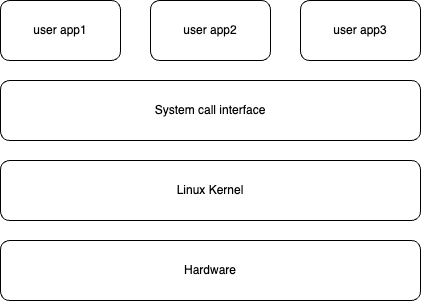

The file system, as a core underlying component of the operating system, is responsible for frequent operations on storage devices. It was initially designed entirely in kernel space. The kernel concept emerged as computer hardware and software became increasingly complex, and operating systems separated the code for managing underlying resources from user programs.

Kernel space and user space

Kernel space:

- The kernel is code with super privileges. It manages a computer’s core resources, such as CPU, memory, storage, and network.

- When kernel code runs, the program enters kernel space, enabling full access to and control over underlying hardware. Due to the kernel’s high privileges, its code must undergo stringent testing and verification, and ordinary users cannot modify it freely.

User space:

- It’s the code of various applications we commonly use, such as browsers and games.

- In user space, the permissions of programs are strictly limited and cannot directly access important underlying resources.

If an application needs to use a file system, it must access it through the interface designed by the operating system, such as the commonly used OPEN, READ, and WRITE, which are system calls. The role of system calls is to build a bridge between user space and kernel space. Modern operating systems often define hundreds of system calls, each with its own clear name, number, and parameters.

When an application makes a system call, it enters a section of kernel space code and returns the results to user space after execution. It’s worth noting that this entire process from user space to kernel space and then back to user space belongs to the same process category.

Virtual file systems

After understanding the background knowledge above, we’ll briefly explain how user space and kernel space interact when a user calls a file system interface.

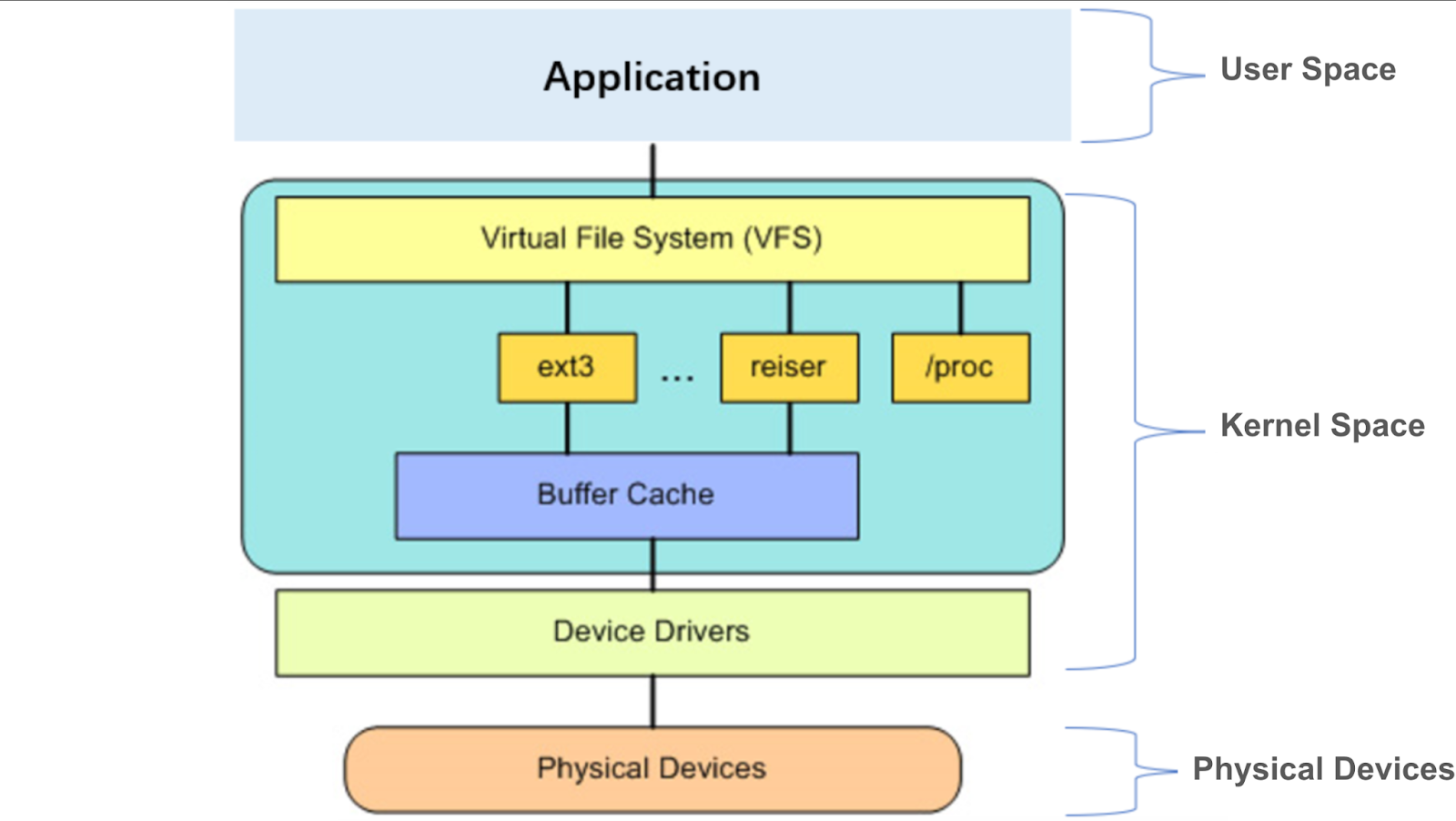

The kernel encapsulates a set of universal virtual file system interfaces through virtual file system (VFS), exposes them to user space via system calls, and provides programming interfaces to the underlying file systems. The underlying file systems need to implement their own file system interfaces according to the VFS format.

The standard process for user space to access the underlying file system: a system call -> the VFS -> the underlying file system -> the physical device

For example, when we call open in an application, it carries a path as its parameter. After this call reaches the VFS layer, the VFS searches level by level in its tree structure based on this path. Ultimately, it finds a corresponding target and its affiliated underlying file system. This underlying file system also has its own implementation of the open method. Then, it passes this open call to the underlying file system.

The Linux kernel supports dozens of different file systems. For different storage media such as memory or networks, different file systems are used for management. The most critical point is that the extensibility of VFS enables the Linux system to easily support a variety of file systems to meet various complex storage needs; at the same time, this extensibility also provides a foundation for FUSE to implement kernel-space functions in user space later.

Network file systems: Breaking kernel boundaries

With the growth of computing needs, the performance of a single computer gradually could not meet the increasing computing and storage requirements. People began to introduce multiple computers to share the load and improve overall efficiency.

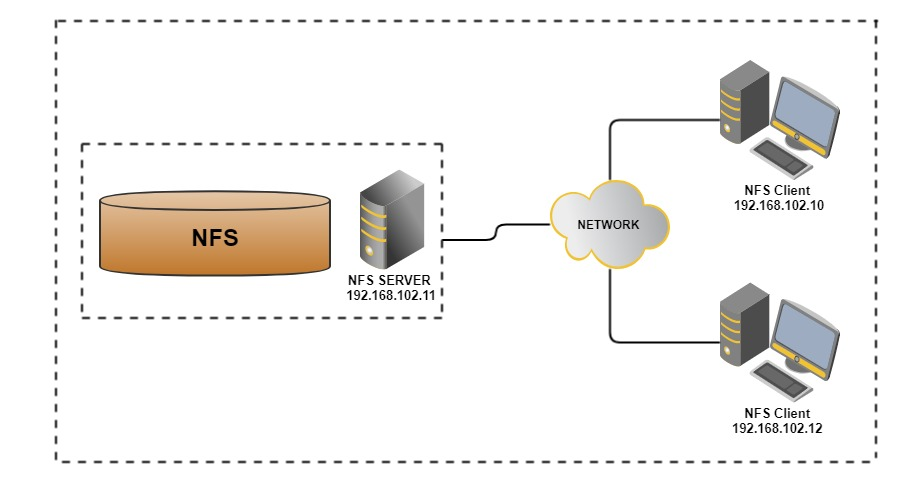

In this scenario, an application often needs to access data distributed on multiple computers. To solve this problem, people proposed the concept of introducing a virtual storage layer in the network, virtually mounting the remote computer's file system (such as a certain directory) through a network interface to the local computer's node. The purpose of this is to enable the local computer to seamlessly access remote computer data as if the data was stored locally.

Specifically, if a local computer needs to access remote data, a subdirectory of the remote computer can be virtually mounted to a node of the local computer through a network interface. In this process, the application does not need to make any modifications and can still access these paths through standard file system interfaces as if they were local data.

When the application performs operations on these network paths (such as hierarchical directory lookup), these operations are converted into network requests and sent to the remote computer in the form of remote procedure call (RPC) for execution. After receiving these requests, the remote computer performs corresponding operations (such as finding files and reading data) and returns the results to the local computer.

The process above is a simple implementation of the NFS protocol. As a network file system protocol, NFS provides an efficient solution for resource sharing between multiple computers. It allows users to mount and access remote file systems as conveniently as operating local file systems.

Traditional file systems typically run entirely in the kernel space of a single node, while NFS was the first to break this limitation. The server-side implementation combines kernel space with user space. The subsequent design of FUSE was inspired by this approach.

FUSE: File system innovation from kernel to user space

With the continuous development of computer technology, many emerging application scenarios require using custom file systems. Traditional kernel-space file systems have high implementation difficulties and version compatibility issues. The NFS architecture first broke through the limitations of the kernel.

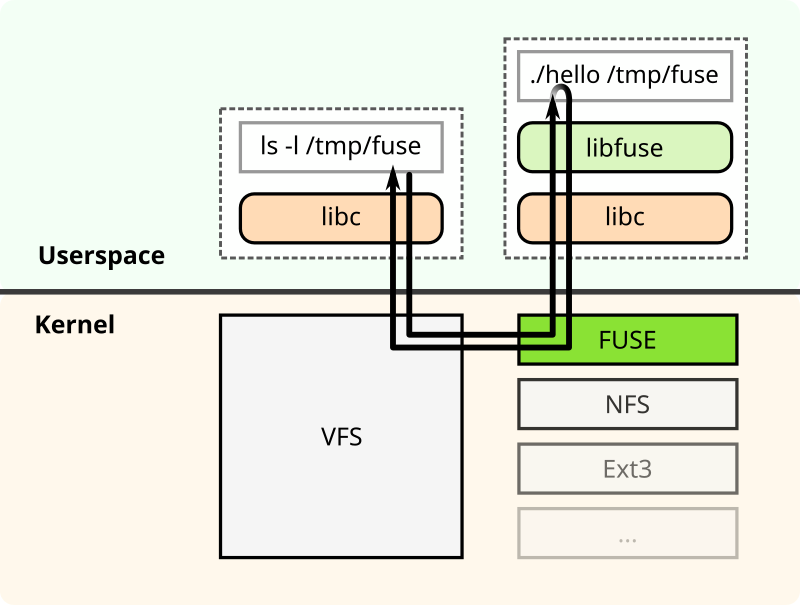

Based on this, someone proposed an idea: Can we transplant the NFS network protocol to a single node, transfer the server-side functionality to a user-space process, while retaining the client running in the kernel, and use system calls instead of network communication to realize file system functions in user space? This idea eventually led to the birth of FUSE.

In 2001, Hungarian computer scientist Miklos Szeredi introduced FUSE, a framework that allows developers to implement file systems in user space. The core of FUSE is divided into two parts: the kernel module and the user-space library (libfuse).

Its kernel module, as part of the operating system kernel, interacts with VFS, forwarding file system requests from VFS to user space, and returning the processing results of user space to VFS. This design allows FUSE to implement custom file system functions without modifying kernel code.

The FUSE user-space library (libfuse) provides an API library that interacts with the FUSE kernel module and helps users implement a daemon running in user space. The daemon handles file system requests from the kernel and implements specific file system logic.

In specific implementations, the user-space daemon and kernel module collaborate through the following steps to complete file operations:

- Request reception

1.1 The kernel module registers a * character device (/dev/fuse) as a communication channel. The daemon reads requests from this device by calling read().

1.2 If the FUSE request queue of the kernel is empty, read() enters a blocking state. At this time, the daemon pauses execution and releases CPU until a new request appears in the queue (implemented through the kernel's wait queue mechanism).

1.3 When an application initiates a file operation (such as open and read), the kernel module encapsulates the request into a specially formatted data packet and inserts it into the request queue, waking the blocked daemon.

-

Request processing

After the daemon reads the request data packet from the character device, it calls the corresponding user-space processing function according to the operation type (such as reading, writing, and creating a file). -

Result returning

After processing is complete, the daemon serializes the result (such as the content of the read file or error code) according to the FUSE protocol format and writes the data packet back to the character device throughwrite().

After the kernel module receives the response:

3.1 It parses the data packet content and passes the results to the waiting application.

3.2 It wakes up the system call blocked in the application to continue executing subsequent logic.

The emergence of FUSE brought revolutionary changes to file system development. By migrating the implementation of file systems from kernel space to user space, FUSE significantly reduced development difficulty, improved system flexibility and extensibility, and was widely applied in various scenarios such as network file systems, encrypted file systems, and virtual file systems.

JuiceFS: A FUSE user-space distributed file system

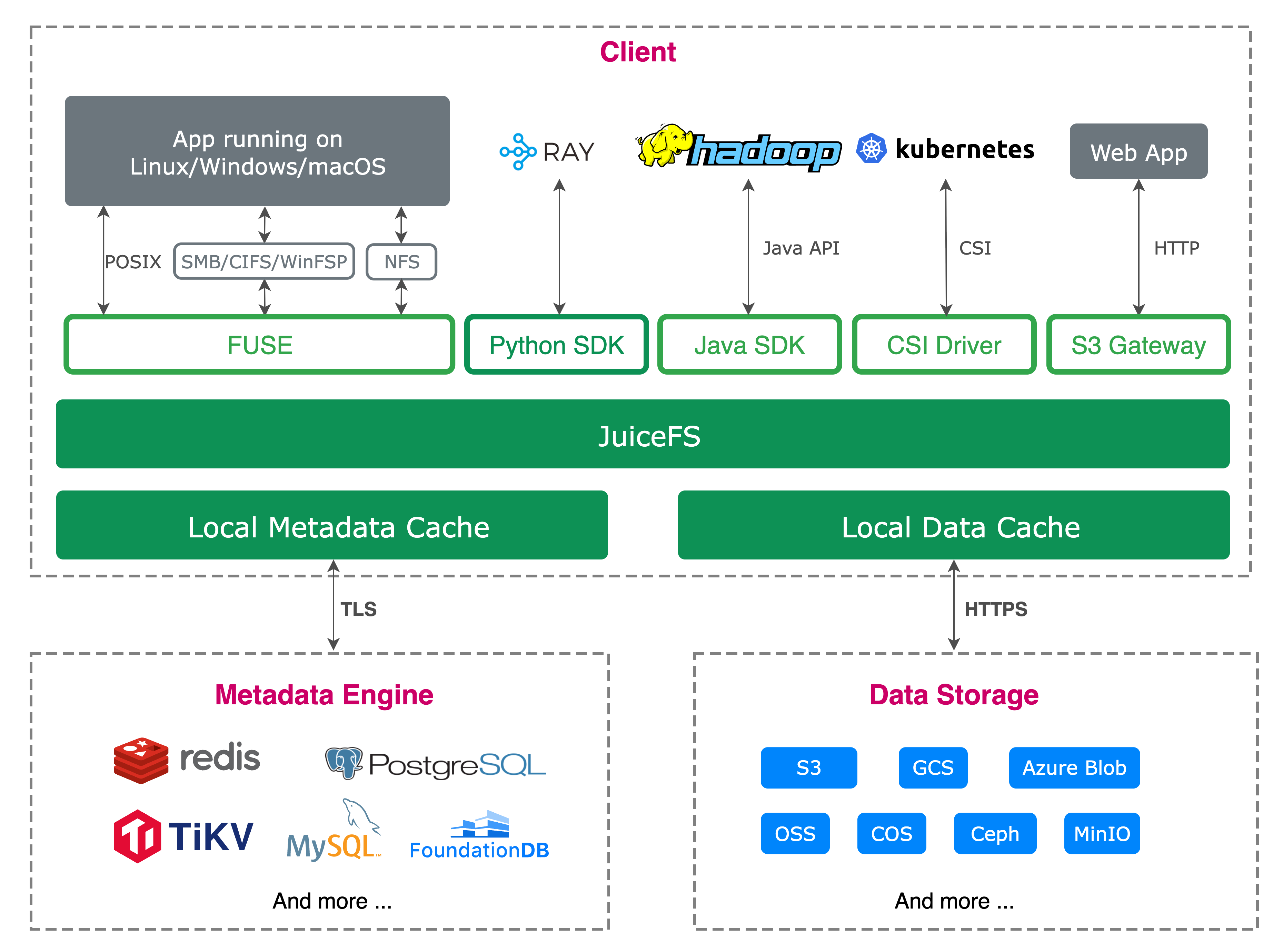

In 2017, with the full entry of IT infrastructure into the cloud era, the architecture faced unprecedented challenges. In this background, JuiceFS was born. As a distributed file system based on object storage, it uses FUSE technology to build its file system architecture, using FUSE’s flexible extensibility to meet the diverse needs of cloud computing environments.

Through FUSE, the JuiceFS file system can be mounted to servers in a POSIX-compatible manner. It treats massive cloud storage as local storage. Common file system commands, such as ls, cp, and mkdir, can be used to manage files and directories in JuiceFS.

Let’s take a user mounting JuiceFS and then opening one of its files as an example. The request first goes through the kernel VFS, then is passed to the kernel's FUSE module, and communicates with the JuiceFS client process through /dev/fuse device. The relationship between VFS and FUSE can be simply regarded as a client-server protocol, with VFS acting as the client requesting service, and the user-space JuiceFS acting as the server role, handling these requests.

The workflow is as follows:

- After JuiceFS is mounted, the

go-fusemodule inside JuiceFS opens/dev/fuseto obtainmount fdand start several threads to read the FUSE requests of the kernel. - The user calls the

openfunction, enters the VFS layer through the C library and system call, and the VFS layer transfers the request to the kernel's FUSE module. - The kernel FUSE module puts the

openrequest into the queue corresponding to thefdofjuicefs mountaccording to the protocol and wakes up the read request thread ofgo-fuseto wait for the processing result. - The user-space

go-fusemodule reads the FUSE request and calls the corresponding implementation of JuiceFS after parsing the request. go-fusewrites the processing result of this request intomount fd, that is, into the FUSE result queue, and then wakes up the application waiting thread.- The application thread is awakened, gets the processing result of this request, and then returns to the upper layer.

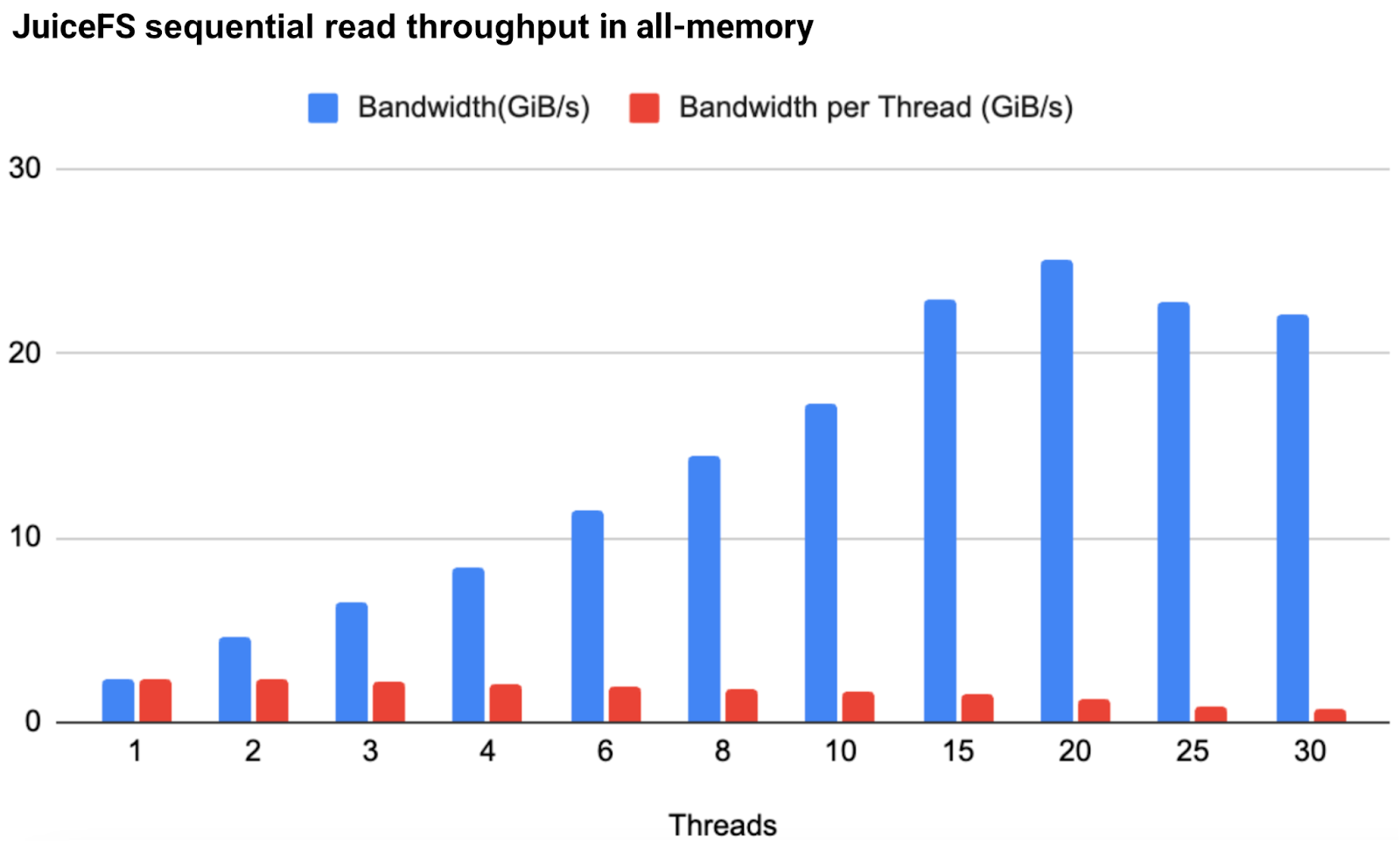

Due to the frequent switching between user space and kernel space required by FUSE, many people have doubts about its performance. In fact, this is not entirely the case. We conducted a set of tests using JuiceFS.

The testing environment: 1.5 TB RAM, an Intel Xeon 176-core machine, a 512 GB sparse file on JuiceFS

We used fio to perform sequential read tests on it:

- Mount parameters:

./cmd/mount/mount mount --no-update --conf-dir=/root/jfs/deploy/docker --cache-dir /tmp/jfsCache0 --enable-xattr --enable-acl -o allow_other test-volume /tmp/jfs - The fio command:

fio --name=seq_read --filename=/tmp/jfs/holefile --rw=read --bs=4M --numjobs=1 --runtime=60 --time_based --group_reporting

This excluded the constraints of hardware disks and tested the limit bandwidth of the FUSE file system.

Testing results:

- The single-thread bandwidth under a single mount point reached 2.4 GiB/s.

- As the number of threads increased, the bandwidth could grow linearly. At 20 threads, it reached 25.1 GiB/s. This throughput already meets most actual application scenarios.

In terms of the use of FUSE, JuiceFS has implemented the smooth upgrade feature. By ensuring the consistency of mount fd, users can upgrade the JuiceFS version or modify the mount parameters without re-mounting the file system and interrupting the application. For details, see Smooth Upgrade: Implementation and Usage.

FUSE also has some limitations. For example, processes accessing the FUSE device require high permissions, especially in container environments, usually requiring privileged mode to be enabled. In addition, containers are usually transient and stateless. If a container exits unexpectedly and data is not written to disk in time, there is a risk of data loss.

Therefore, for Kubernetes scenarios, the JuiceFS CSI Driver allows applications to access the JuiceFS file system with non-privileged containers. The CSI driver manages the lifecycle of the FUSE process to ensure that data can be written to disk in time and will not be lost. For details, see K8s Data Persistence: Getting Started with JuiceFS CSI Driver.

Conclusion

FUSE decouples user space from kernel space, providing developers with great flexibility and convenience in implementing file systems in user space. Especially in modern computing environments such as cloud computing and distributed storage, FUSE makes building and maintaining complex storage systems more efficient, customizable, and easy to expand.

JuiceFS is based on FUSE and implements a high-performance distributed file system in user space. In the future, we’ll continue exploring optimization methods for FUSE and continuously improving the performance and reliability of file systems to meet increasingly complex storage needs and provide users with stronger data management capabilities.

If you have any questions for this article, feel free to join JuiceFS discussions on GitHub and community on Slack.