juicefs sync is a powerful data synchronization tool that supports data transfer between object storage, JuiceFS, and local file systems. It can maximize the efficiency of large-scale full migrations, achieving transfer speeds close to the upper limit of the network bandwidth. This makes petabyte-level data migration feasible within days or weeks (the actual duration depends on bandwidth and cloud throttling policies). Beyond this, it also supports accessing remote directories via SSH, HDFS, and WebDAV, while offering advanced features such as incremental synchronization, pattern matching (similar to rsync), and distributed synchronization.

In this article, we’ll focus on the core execution principles of sync, introducing its architecture and task scheduling mechanisms in both standalone and cluster modes. We’ll also provide a detailed explanation of how performance is improved through concurrency optimizations. In addition, the article will cover sync’s multi-dimensional filtering capabilities, flexible path-based pattern matching, and data consistency verification mechanisms. We aim to help users better understand and utilize this tool for efficient and reliable data synchronization.

How it works

The core execution principle of sync is consistent between standalone mode and cluster mode. The main differences lie in the deployment approach and the task distribution mechanism. Therefore, this section uses standalone mode as an example to explain the principles. We’ll explain the differences in cluster mode later.

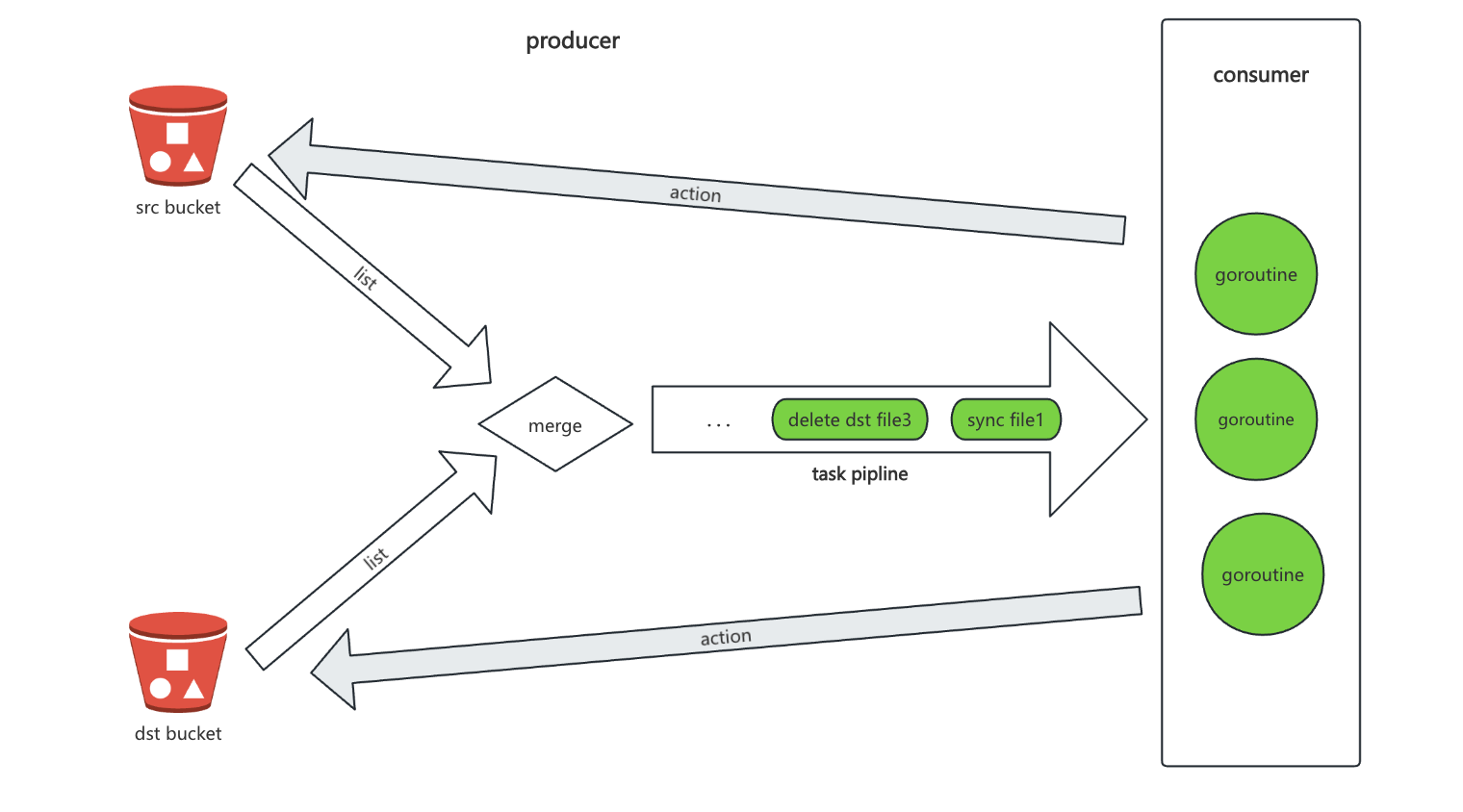

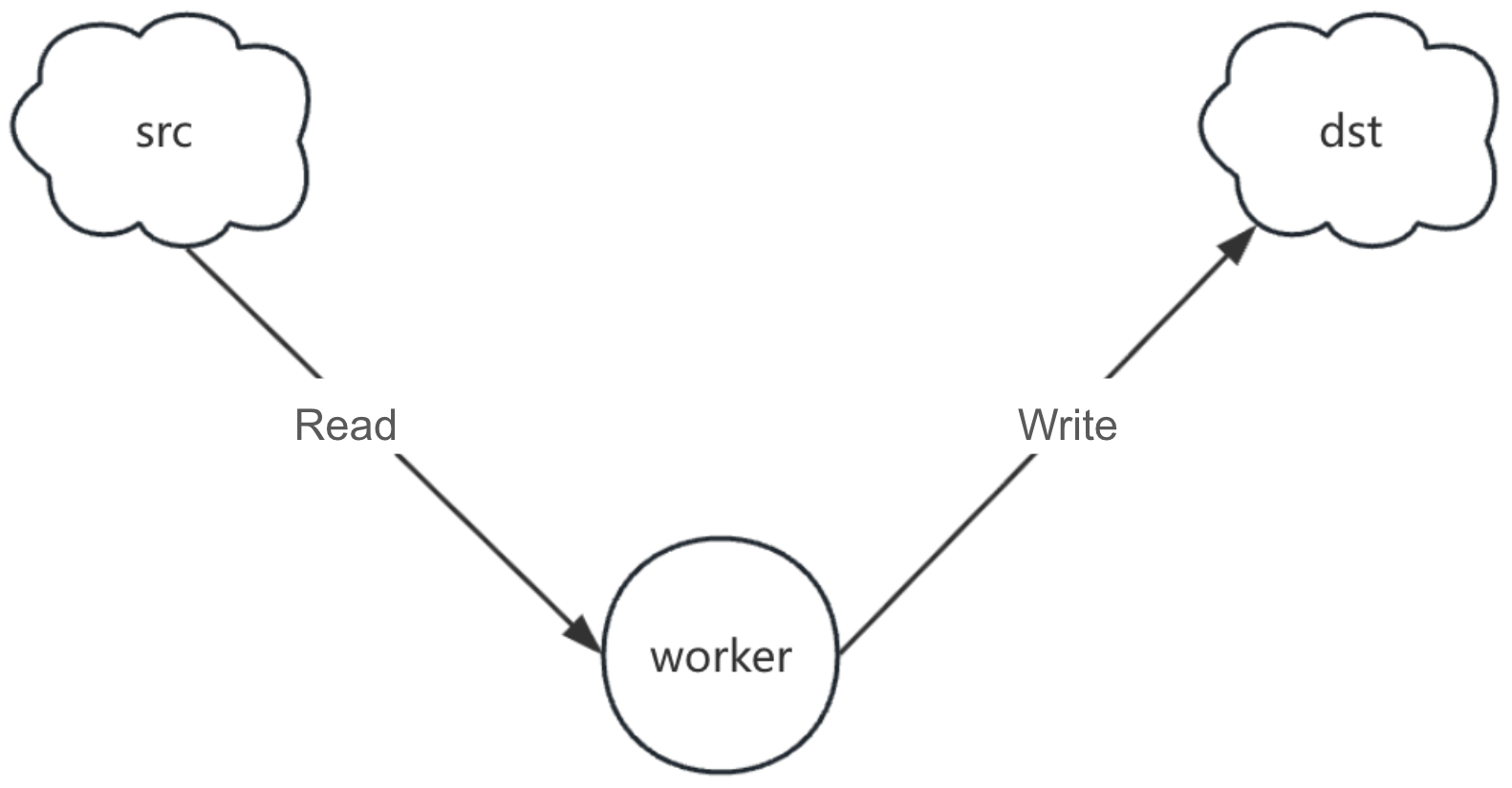

As shown in the figure below, we can abstract the architecture of sync as a typical producer–consumer model:

- The producer traverses all keys in the source and target object storage, merges the ordered results from both ends, determines whether objects need to be synchronized, deleted, or validated based on this, and writes the generated tasks into a task queue.

- The consumer continuously retrieves tasks from the queue and performs the actual operations.

In standalone mode, the producer and consumer run within the same process and collaborate concurrently through goroutines (lightweight threads).

At the producer stage, the reason for simultaneously traversing the target end is that sync synchronizes data from the source and also supports the deletion of redundant objects on the target according to configuration. By combining the existence and different status of objects on the target, it determines what type of task to generate for each key. Currently, it supports five types of tasks: sync, delete from source, delete from target, copy permissions, and verify.

Next, we’ll further elaborate on the specific mechanism of task generation at the producer stage.

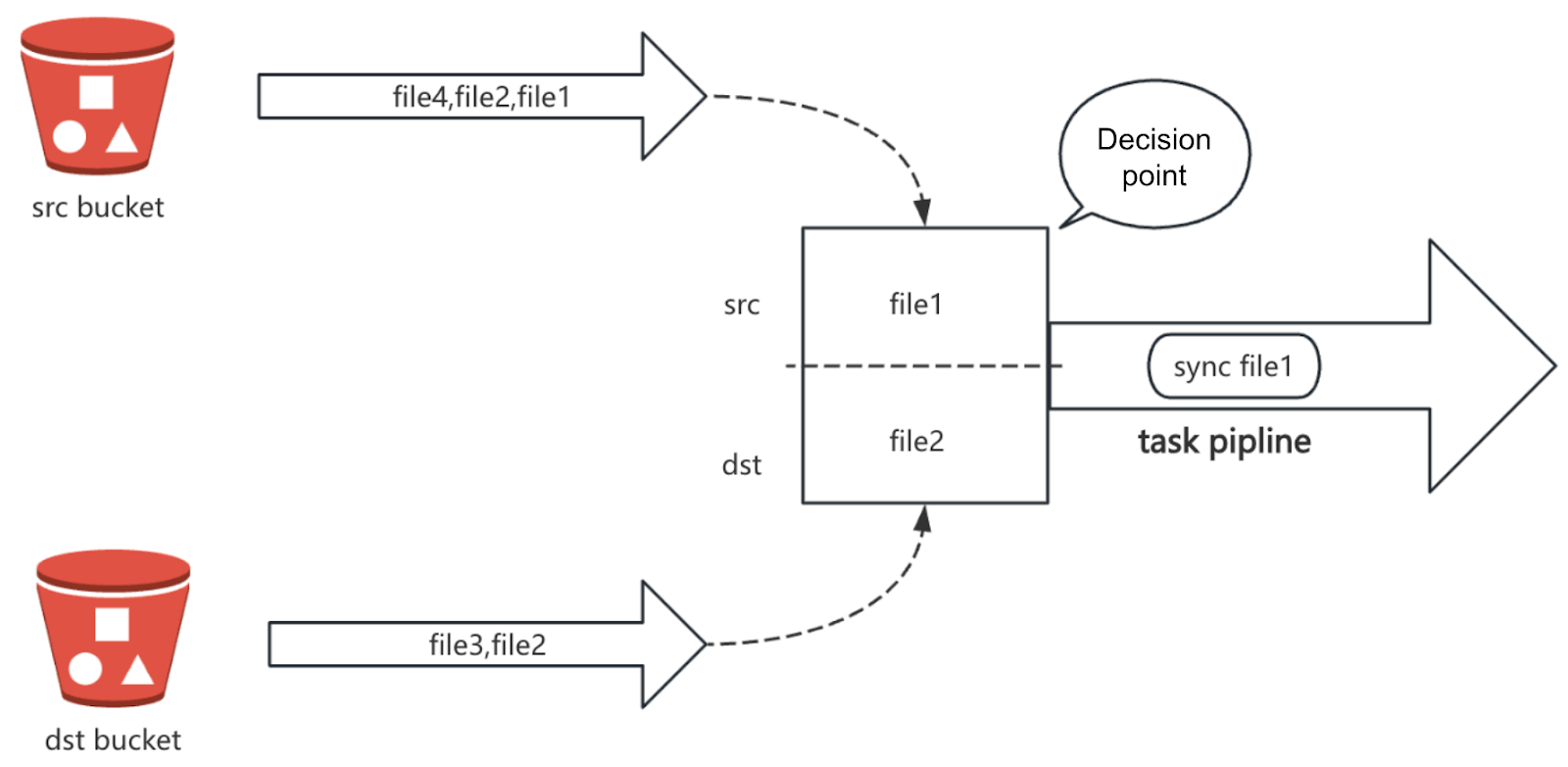

To improve task generation efficiency, sync requires that the traversal (list) interface of the object storage must return results in an ordered manner, that is, sorted by key in ascending order (such as lexicographically). Relying on this ordering, the producer can perform linear scans on both the source and target object storage simultaneously and compare the current key values one by one to determine whether a synchronization task needs to be generated.

Taking the merge process shown in the figure as an example, sync traverses the source and target synchronously. It reads the key at the current position from each side, for example, file1 from the source and file2 from the target:

juicefs sync file filtering workflow:

- If

src key<dst key(for example,file1<file2), a synchronization task is generated. Then, the source pointer moves forward to continue comparing with the current target key. - If the keys at both ends are the same (for example, both are

file2), it means the object exists on both sides. Whether to skip or perform further verification can be judged based on policy. Both pointers then move forward simultaneously. - If

src key>dst key(for example,file4>file3), it indicates an extra object exists on the target. This possibly requires a deletion task. Then, the target pointer moves forward.

The comparison logic continues until all keys from both source and target have been traversed. Thereby this constructs a complete task queue. The primary advantage of this strategy is that it requires only a linear scan to assess the state of all objects and quickly generate tasks.

Performance optimization

After understanding what the producer and consumer do, let’s examine where performance bottlenecks mainly occur and how to optimize them.

Produce optimization

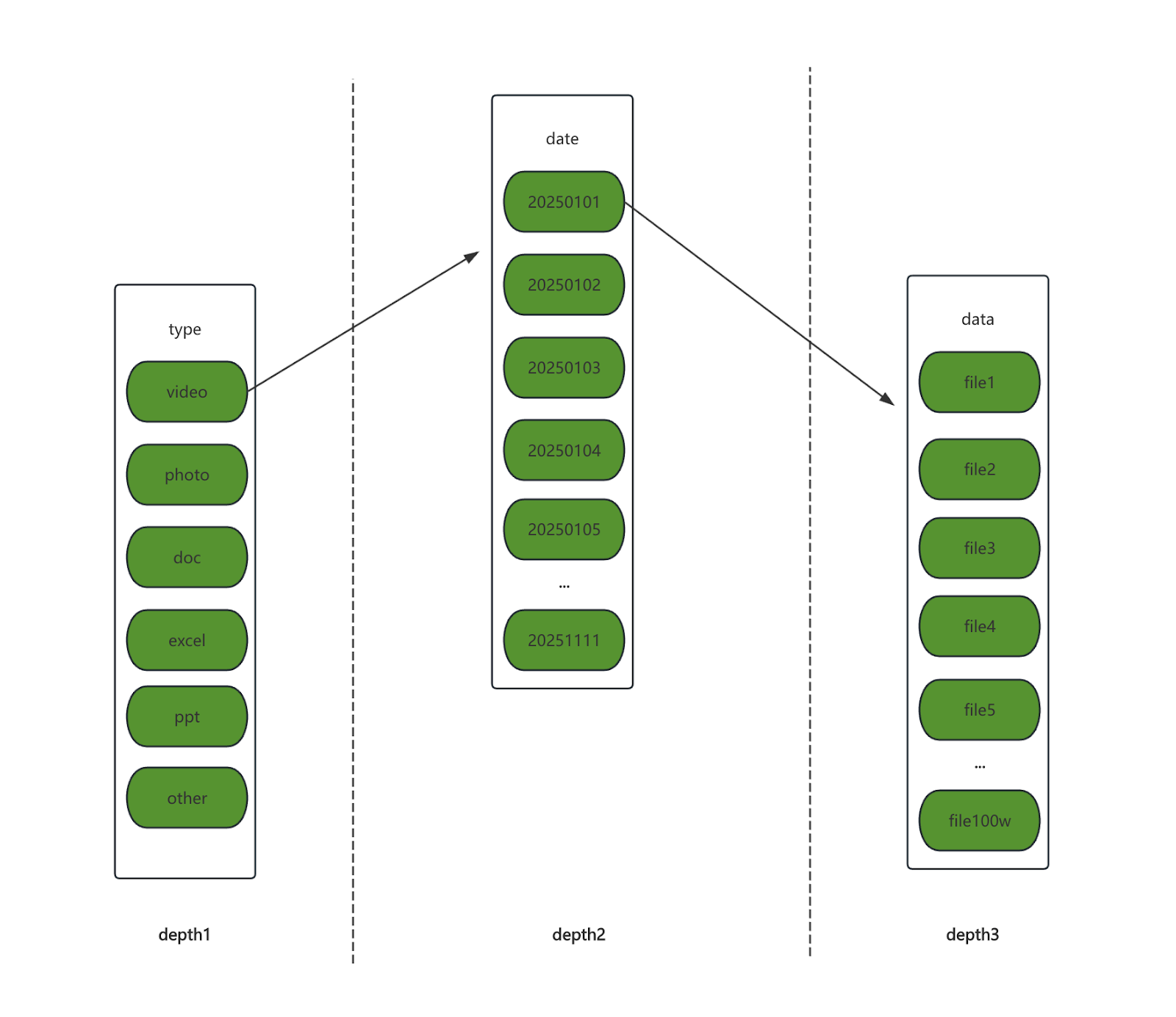

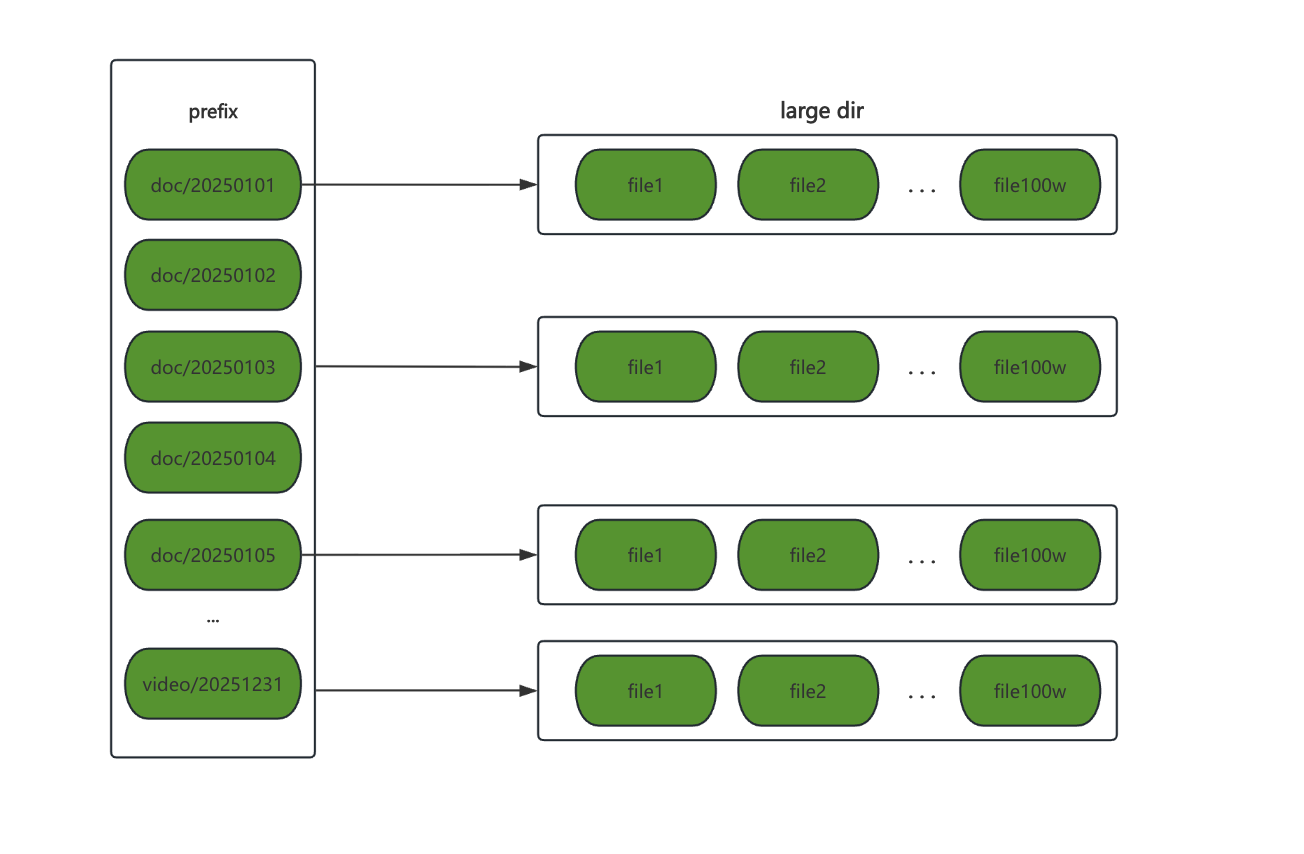

During producer execution, list operations on object storage can become a performance bottleneck. The list interfaces of most object storage systems do not support specifying a range to return results for a particular interval, unlike segmented downloads where list operations for the same directory can be split into multiple intervals for parallel execution. Therefore, sync's optimization strategy is: execute list operations sequentially within a single directory, but execute list operations concurrently across multiple directories, and then aggregate the results from each directory into a complete key set.

In terms of the traversal method:

- The first step is a breadth-first traversal with limited depth on the directory tree to find all subdirectories. This achieves directory-level splitting.

- The second step involves a full traversal of each subdirectory, listing all objects under that prefix. This step requires that the list of objects be ordered.

Consumer optimization

The entire transfer process is an end-to-end pipeline: the consumer reads data from the source and writes it directly to the target, without passing through the local disk. Therefore, any bottleneck in either reading from the source or writing to the target can become a bottleneck in the synchronization flow.

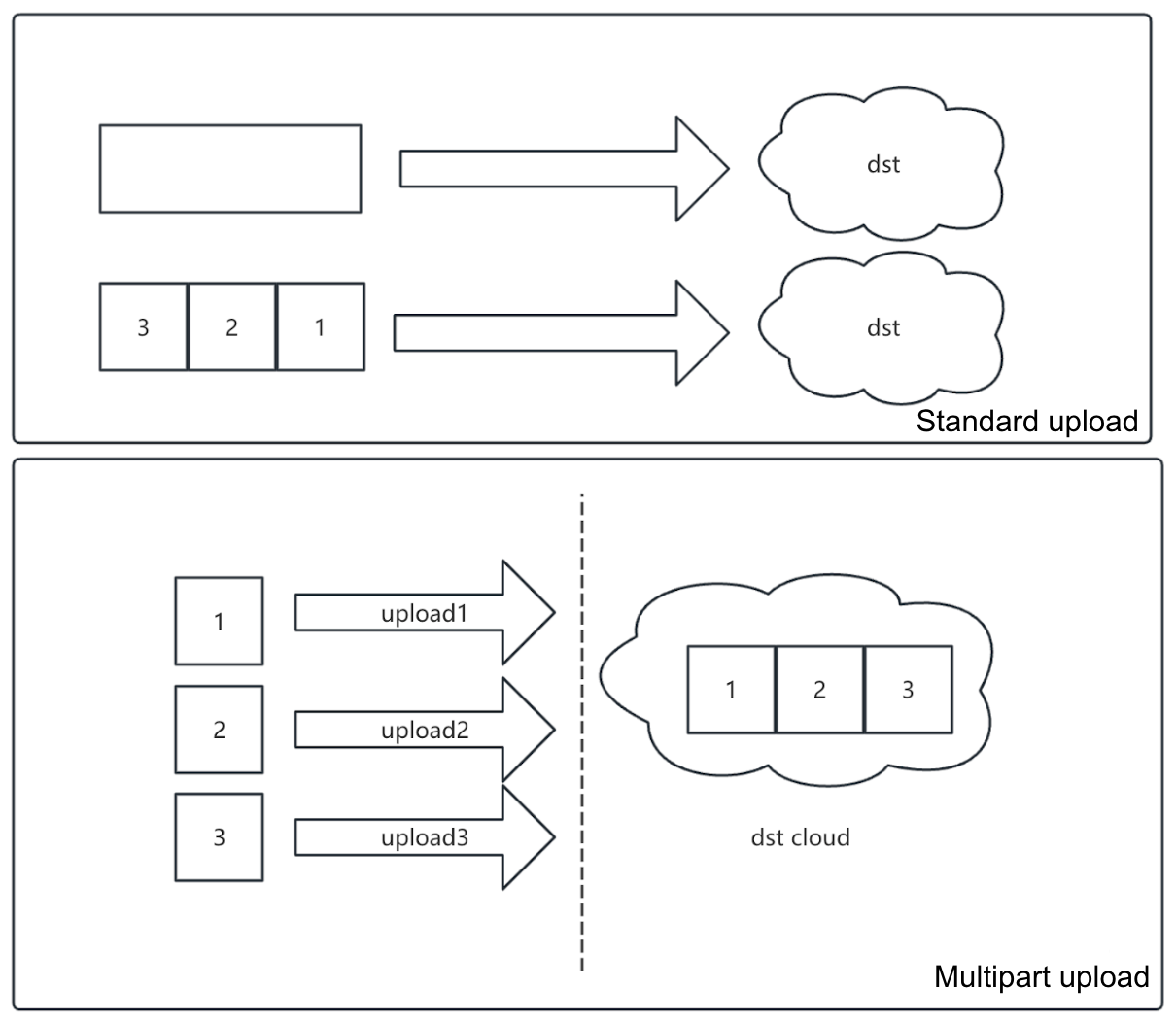

During the upload process, sync supports concurrent execution of multiple tasks, handled by multiple goroutines. From a task perspective, the system possesses a degree of parallel transmission capability. The optimization focus is on enhancing read/write concurrency for large files.

Therefore, sync utilizes the object storage's multipart upload capability. It splits a large file into multiple parts, uploads them in parallel via multiple goroutines, and finally completes the merge via a combine interface.

For extremely large files, we can further split the parts:

- Upload several intermediate objects.

- Use the

UploadPartCopyinterface to perform splitting and merging of these intermediate objects directly within the object storage service.

This two-level splitting + two-level merging for the same file significantly improves the concurrency and efficiency of large file transfers.

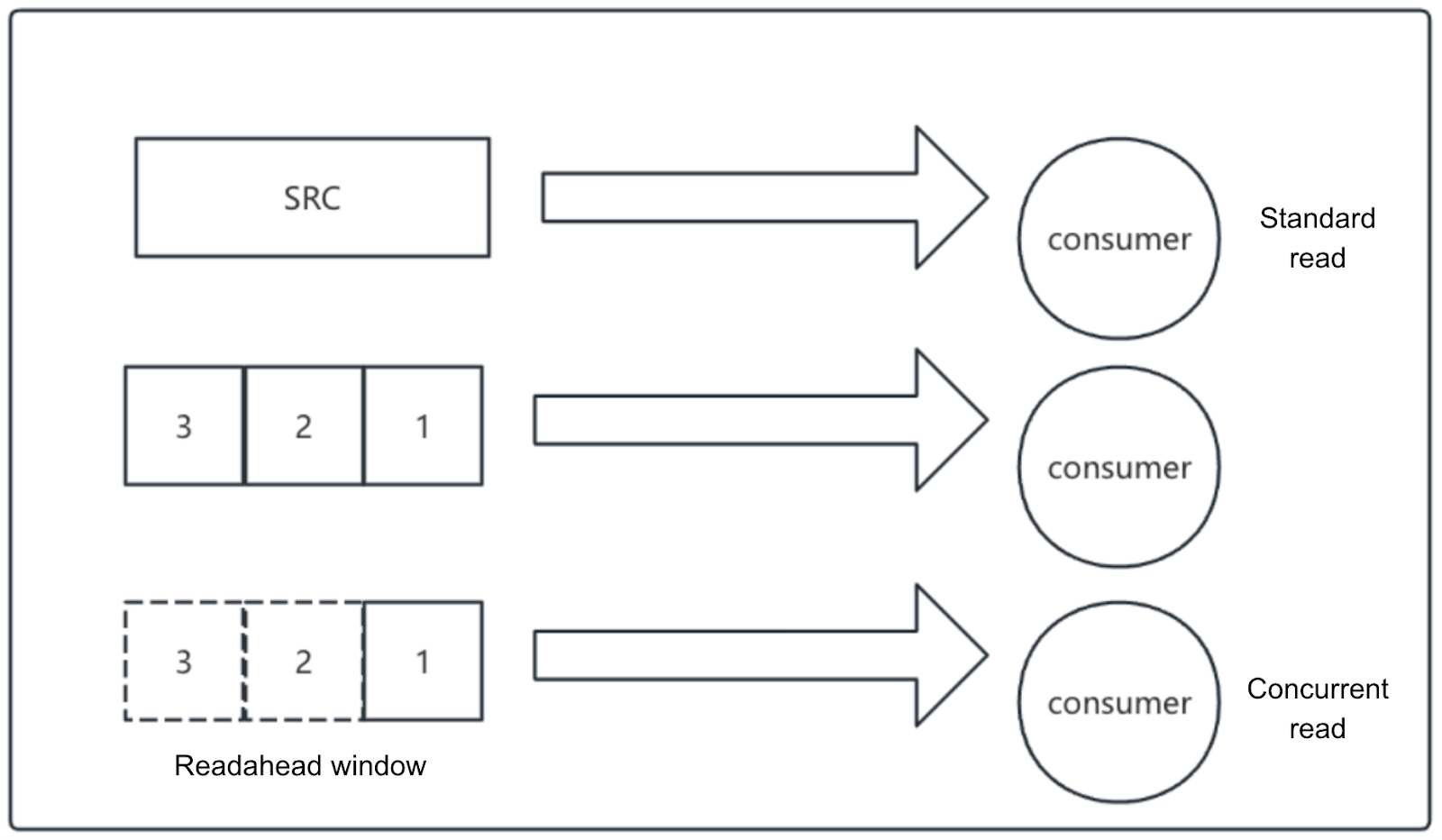

Compared to the write path, the read-side concurrency logic is simpler: split the object into chunks and read each chunk concurrently. These concurrently read chunks form a readahead window. This means data blocks ahead of the current read position (offset) are pre-downloaded and cached as much as possible. The readahead mechanism helps reduce wait times when source read performance is insufficient or network jitter occurs, preventing the read side from becoming the performance bottleneck in the transfer pipeline.

Cluster mode

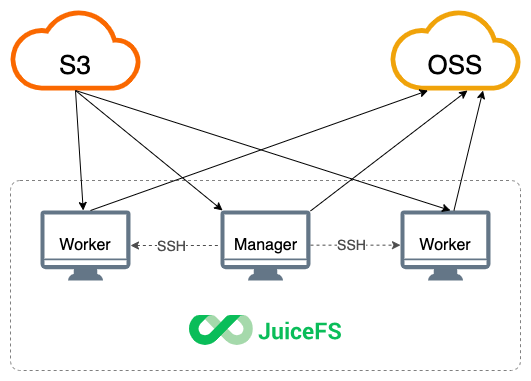

For larger data scales where single-node throughput is insufficient, sync also supports cluster mode. By horizontally scaling workers across multiple nodes to execute tasks in parallel, overall synchronization efficiency can be further enhanced.

Cluster mode does not introduce a new synchronization algorithm. The changes relative to standalone mode are mainly reflected in the physical deployment method and task distribution channels.

Physical deployment differences

In standalone mode, the producer and consumer run within the same process, cooperating via different goroutines. In cluster mode, consumers can be independently deployed to multiple nodes as worker nodes, while the producer serves as the manager node. This enables horizontal scaling.

Before enabling cluster mode, SSH password-free login needs to be configured between the manager and each worker node. After starting cluster mode, the manager distributes the juicefs binary to the /tmp directory of each worker node and starts the worker process remotely via SSH to join the synchronization task.

Task distribution mechanism differences

In standalone mode, the producer and consumer pass tasks via Go's chan within the same process. In cluster mode, task distribution switches to an HTTP-based approach—the manager provides a task allocation API, and each worker periodically polls the manager to pull tasks for execution. Except for the communication method, the rest of the flow is consistent with standalone mode.

Task filtering

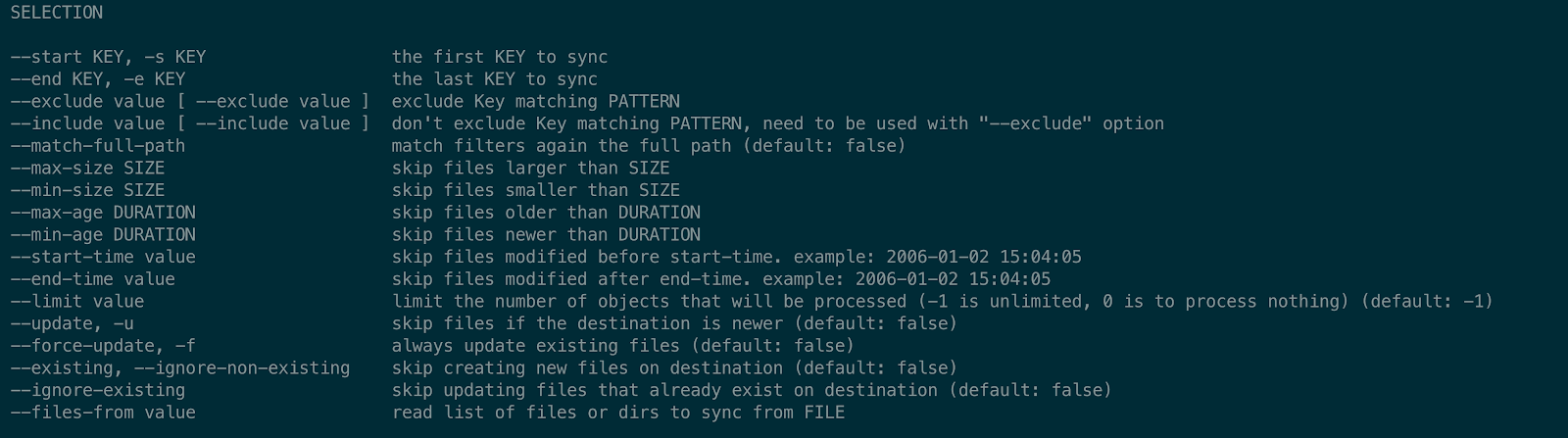

In real-world synchronization scenarios, users typically only want to perform synchronization or cleanup operations on objects meeting specific criteria. sync supports filtering objects from multiple dimensions during the task generation stage and decides whether to generate a task and its type based on the filtering results. Overall, filtering and adjustment mainly include the following categories:

- Based on time: Filter keys according to the file's

mtime. - Based on size: Filter keys according to the file's size.

- Based on key: Filter keys through pattern matching rules for paths/names.

- Based on result: Filter or adjust task types by combining the key's existence status or differences on the target.

Among these, filtering based on key is the most commonly used and flexible. sync uses the --exclude and --include parameters for path pattern matching to precisely control the synchronization scope.

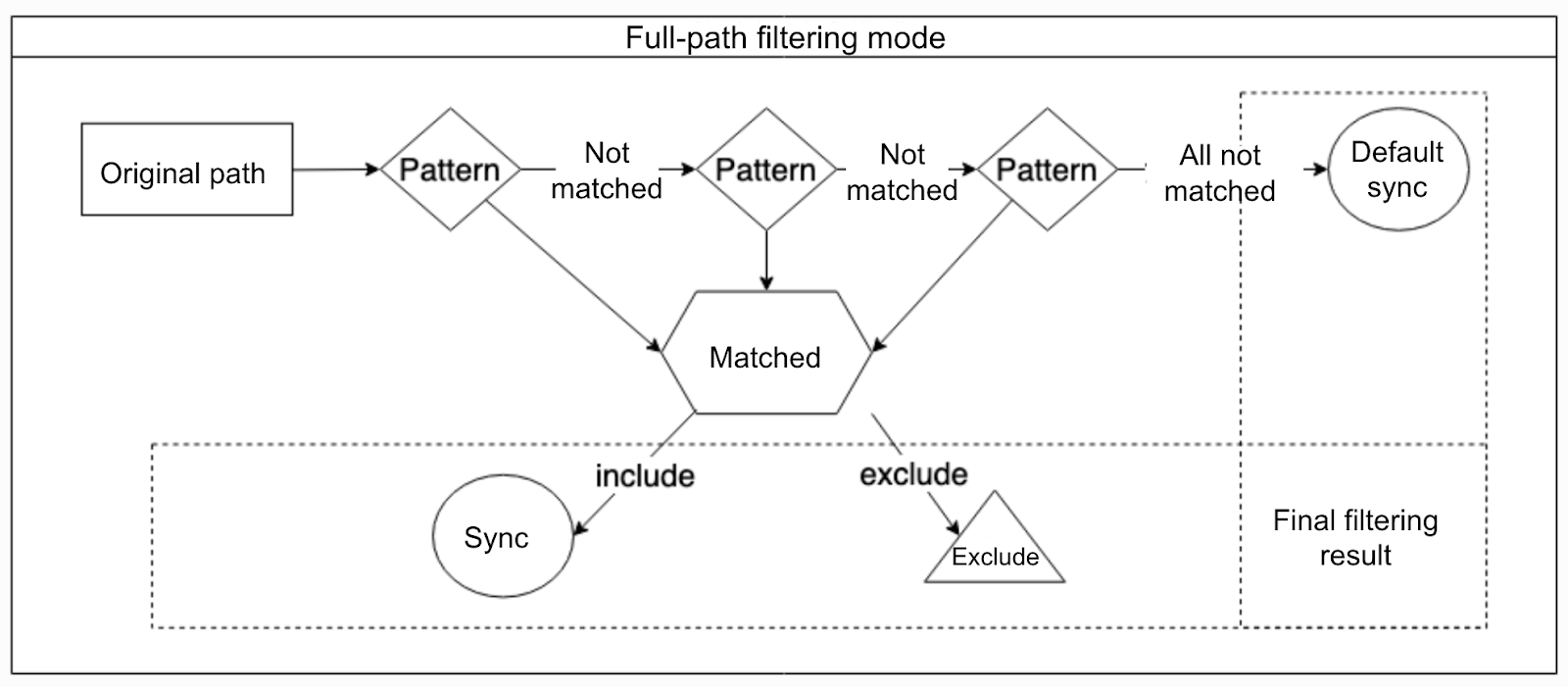

Currently, two matching modes are supported: the layer-by-layer filtering mode and the full-path filtering mode. The layer-by-layer mode is compatible with rsync's rules but complex to use. For details, see this document. The following will focus on the more intuitive and easier-to-use full-path filtering mode.

Since v1.2.0, the sync command added the --match-full-path option to enable the full-path filtering mode. In this mode, sync will match the full path of the object to be processed sequentially against multiple configured rules. Once a rule is matched, the processing result for that object (synchronize or exclude) is immediately determined, and subsequent rules are no longer evaluated.

For example, consider a file with the a1/b1/c1.txt path and three matching patterns: --include 'a*.txt', --include 'c1.txt', and --exclude 'c*.txt'. In full-path filtering mode, the string a1/b1/c1.txt is directly evaluated against the patterns sequentially:

- Evaluate

a1/b1/c1.txtagainst--include 'a*.txt'. The result is no match because*cannot match the/ character. See Matching rules. - Evaluate

a1/b1/c1.txtagainst--include 'c1.txt'. According to the matching rules, this will match successfully. Although the subsequent--exclude 'c*.txt'would also match according to the rules, based on the logic of the full-path filtering mode, once a pattern is matched, subsequent patterns are no longer attempted. Therefore, the final match result is "synchronize".

More examples:

--exclude '/foo**'excludes all files or directories whose root directory name isfoo.--exclude '**foo/**'excludes all directories ending withfoo.--include '*/',--include '*.c', and--exclude '*'includes only all directories and files with the.csuffix; all other files and directories are excluded.--include 'foo/bar.c'and--exclude '*'includes only thefoodirectory and thefoo/bar.cfile.

Data integrity verification

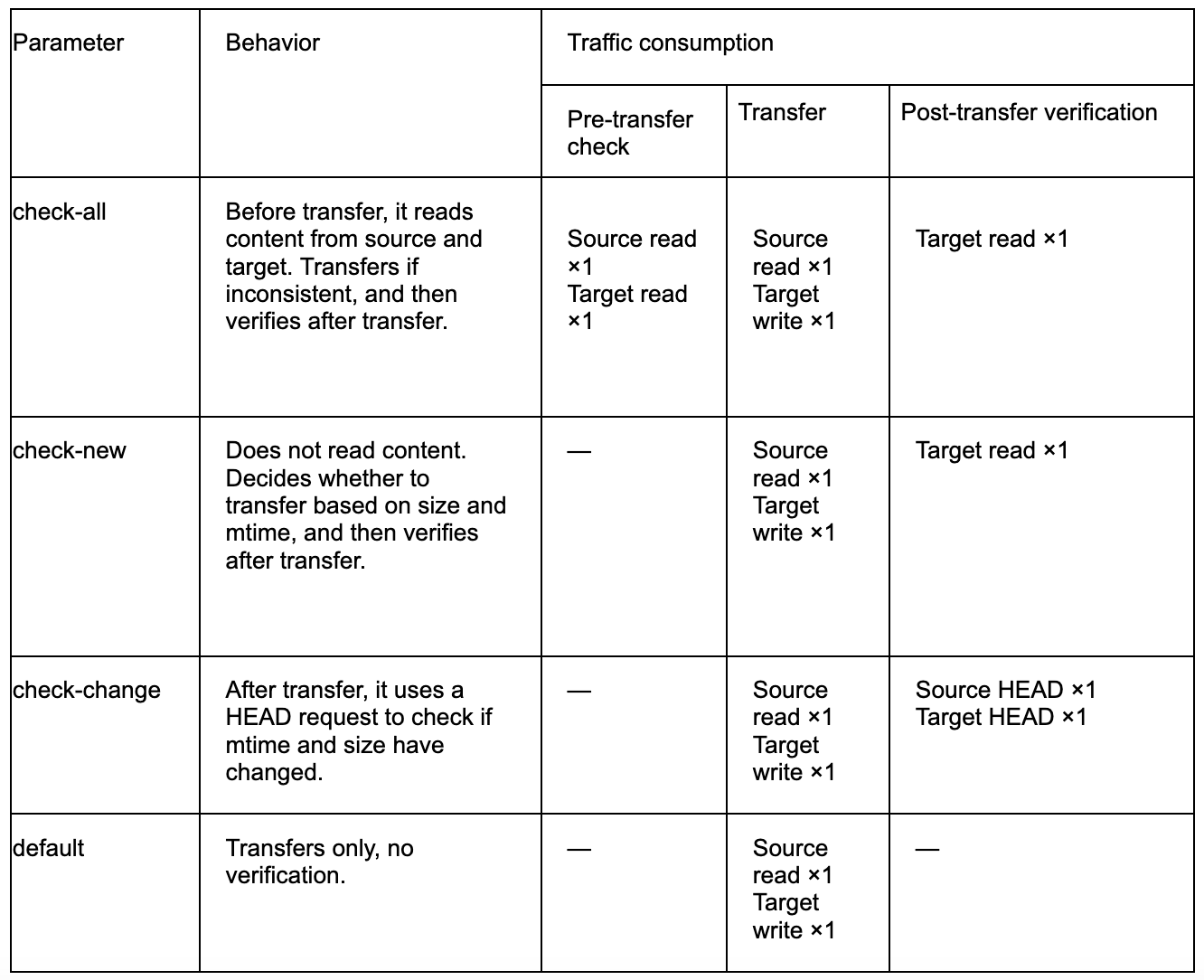

Beyond high-concurrency transfers, correctness of the synchronization result is crucial. To mitigate risks from network jitter, concurrent writes during synchronization, and differences in consistency semantics across storage backends, juicefs sync provides a multi-level data integrity verification mechanism. This allows users to balance reliability and resource overhead based on application requirements.

Specifically, sync supports different verification levels when executing sync tasks:

- Stricter verification provides stronger guarantees for data consistency between source and target but introduces higher read amplification and CPU consumption.

- More relaxed verification has less impact on performance but correspondingly increases tolerance for potential inconsistencies.

Users can choose suitable verification parameters based on data importance and performance costs.

Taking the highest-level verification check-all as an example, its process has three steps:

- Pre-transfer comparison: When determining whether an object needs synchronization,

syncreads and compares the data content from the source and target. If the content differs, a synchronization task is generated and executed.

In extreme scenarios, it might be necessary to read to the last byte to confirm inconsistency. At this point, both source and target undergo one full read before the transfer. This results in approximately 1x additional read traffic. - Transfer process verification: During synchronization, source data is read entirely again and written to the target. This results in approximately 1x read traffic on the source and 1x write traffic on the target. Simultaneously,

synccalculates a checksum while reading the source data, obtaining the object's verification value after the read is complete. - Post-transfer verification: To verify the correctness of network transmission and target-side writing,

syncreads the target object once more, calculates its checksum, and compares it with the checksum obtained during the transfer. If they are inconsistent, a data error has occurred, and an error is reported.

The table below shows comparison of sync verification modes and traffic consumption.

check-new can be seen as a subset of check-all: it only performs the above content verification on new or objects requiring transmission to achieve a balance between higher reliability and lower overhead.

check-change adopts a weaker verification approach: it does not directly compare content but infers whether an object has changed based on metadata like mtime and size. Since this strategy does not verify the actual content, there is a possibility that metadata remains unchanged while content is different. Therefore, this offers the lowest verification level with the smallest performance overhead

Conclusion

This article systematically introduced the architectural design, performance optimization, cluster mode, and task filtering mechanisms of juicefs sync. We aim to help users gain a deeper understanding of its implementation principles and usage methods. We’ll continue to optimize and evolve sync.

If you have any questions for this article, feel free to join JuiceFS discussions on GitHub and community on Slack.